| City/Town: • Newkirk |

| Location Class: • School |

| Built: • 1884 | Abandoned: • 2001 |

| Historic Designation: • National Register of Historic Places • Native American Heritage Site • Abandoned Atlas Foundation Contribution to POK Most Endangered List (2011) |

| Status: • Abandoned |

| Photojournalist: • AbandonedOK Team • David Linde • Johnny Fletcher |

WARNING: Chilocco is heavily guarded by 24/7 security. This is not a place for you to get in your car and go visit. This is for your online viewing pleasure only. Because this land is being used by law enforcement as practice and training grounds, it is governed by federal police; not local police. DO NOT ATTEMPT TO VISIT CHILOCCO INDIAN SCHOOL.

Gallery Below

“An institution, founded to transform Indian youth was paradoxically given life by the very people whose tribal identities it was committed to erase”

-K. Tsianina Lomawaima “They call it Prairie Light”

In 1928 an expose of federal Indian Service mismanagement scathingly critiqued conditions in the boarding schools, including Chilocco, and in the early 1930s, some reforms were introduced. Boys and girls could sit together in the dining rooms, more attention was invested in academic work, and drudgery work devoted to school upkeep was cut back. Nonetheless, many aspects of student life endured: separation from home and family for years at a time, devotion to fellow students, strict discipline, and curricula that remained focused more on vocational than academic preparation. A copy of an older Chiloccoan yearly depicts this:

The institution was established and is maintained by the United States Government, not to give its students anything but to loan them each a few hundred dollars’ worths of Board, Clothing, and Tuition. The tuition is in the following lines:

Academic.-This course is the equivalent of the usual High School Course but not the same. Non-essentials are eliminated and one half of each day is given to industrial training and the other half to academic studies. All effort is directed toward training Indian boys and girls for efficient and useful lives under the conditions which they must meet after leaving school.

Vocational.- Special stress is placed upon the courses in Agriculture and Home Economics for these reasons:

1. The Indian has nine chances to earn a livelihood and establish a permanent home in a congenial environment as a farmer to everyone in any other pursuit.

2. His capital is practically all inland, of which he must be taught the value, and which is appreciated as of any considerable value only when he has gained the skill and perseverance by means of which he can make it highly productive.

Our large farm of nearly 9,000 acres offers unusual facilities for giving practical instruction in Farming and Stock raising, Gardening, Dairying, and Horticulture.

The course in Mechanical Arts offers Instruction in Printing, Engineering, Carpentry, Blacksmithing, Masonry, Shoe and Harness Making and Painting.

The girls have furnished instruction in every department of homemaking including Domestic Science and Domestic Art and Nursing. Instruction in instrumental music is provided for those who manifest talent for it.

Vocation at Chilocco was heavily entrenched in the curriculum. The thought was that the Indian students would have a better chance of leading useful and productive lives if they were taught how to live and how to provide rather than be educated as white students in a public school. “Life instruction” was also an aspect of students’ lives. Many could not speak English, could not use a telephone, or write. Enunciation was not only an exercise but a necessity as the soft accents of the Native Americans often came through in the English language they spoke. The development to bring the control of perfect diction was a way the children could come into the mainstream of the American lifestyle. Assimilating the Indians was very much about the limiting of one cultural background in the pursuit of a civilized way of life. Girls were even instructed on how to make a home. As Donna depicts in her article -from Electricscotland.com

“Maybe five or six girls were plucked from the dormitory to spend a short training period by actually staying in the small house or cottage together. The purpose was a kind of living training for being prepared to care for our own homes. Meals were prepared and served at a table instead of at the sterile cafeteria where we normally took our food. The small number at the table created more of a family situation. Napkins, silverware, delicate water glasses made the table setting pleasant. The girls never tired of the ice in their glasses even though it was during the coldest time in the winter. This was a pleasure not normally enjoyed as each had walked through the chow line at Leupp Hall.”

Chilocco emphasized the individual. They taught that personal fulfillment and protection was the most important aspect of life. For many, this was a difficult concept to comprehend. This ideal was a complete juxtaposition to what many students were raised to believe. Tribal life teaches the importance of the greater good of the group, as opposed to the latter. Having been separated from their families, many students struggled to maintain this way of life and often, many ran away because of the difficulty this separation caused. As a resort, many formed what the students called clans. Often they would immediately side with members of their tribe, which, often caused rifts among classmates and along tribal lines.

Later though, the school and its employees began to respect the Native American’s cultural beliefs. Around 1955 the Indian Club was established. It allowed students to practice their beliefs and was open to any student who wished to join.

The campus of Chilocco is centered around the Main oval, with buildings having to do with the operating of the school extending out from its center. All of the original buildings on the campus are constructed out of limestone quarried from the property. They are very imposing structures, enduring, and lasting. [singlepic id=5825 w=210 float=right]Thus giving the campus an appearance of dominance and control. At the north end of the oval is Leupp Hall. This was where all meals were had. Vocations in weaving, cooking and baking, sewing, health and nursing classes, and family values were taught. Social training was taught here also for girls to learn how to put on banquets and parties. On the east side of the building was the bakery which served two purposes. It provided the bread and other pastries for the daily meals of the total student body and was training for boys who wished to work at this as a vocation after they graduated. The kitchen was located in this building and there was the latest equipment in use. Walk-in cold storage stored produce from the school’s orchards and gardens. Great stainless steel vats cooked the food. Beef, mutton, and pork produced by the school were cooked here.

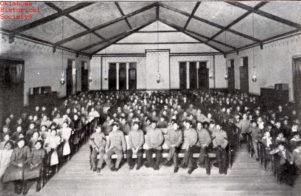

Immediately south of these buildings is the imposing structure on Hayworth Hall. It housed the auditorium, principal’s office, and vocational classes in the basement. The stage in the auditorium was where many different presentations were made for the students’ enjoyment. There was a projector room on top of this room, and this is where movies were shown on a screen. These movies were where girls and boys were allowed to enjoy each other’s company as a kind of date.

The gym and pool buildings are across the oval and behind Home 6. Chilocco was known for its award-winning boxing team which held its practices here, along with the basketball, and the swim teams. Dances and socials as well as pageants took place in the gym. To the west is a newer building, a dormitory for boys. It was built in the 1960s when Chilocco received federal funds to improve the campus. It has two large day areas at its front and a cafeteria. The dorm is three floors, with each room housing 4-6 boys. Students had their own dressing area with a small built in desk and closet. Although this building is the newest structure on the campus it too is in a serious state of disrepair. Broken windows are everywhere. Holes have been punched into the walls and plumbing was been salvaged. Although it is in a dire state, it is important to mention that small memories of past students are drawn on walls. Small drawings and messages to other classmates show the life that was once here.

To the west of this building is the vocational area. Buildings for studies in laundry, drafting, welding, and woodcraft. Here you can still find curriculum scrolled on blackboards and posters. The laundry still has its semester plan which involved classes on how to remove different stains from clothing, and dry cleaning. There are still large pressing machines here. A small gas station and auto shop are directly behind. The fire station and its fire truck are still intact also. The fire engine still gleams red. Emblazoned on its side “Chilocco Indian School Bureau of Indian Affairs”[singlepic id=5766 w=210 float=right]

Staff housing and the school incinerator are to the west of this area, as well as the water tower that looms over the campus. To the north behind Leupp Hall and west are the dormitories that NARCONON refurbished. They have central courtyards and are larger than the girls dorm next to Hayworth Hall. The walls are painted pastel pink and dark green. What they assumed as Native American motifs are painted as borders throughout the buildings. These buildings have a large day room with a grand fireplace and a bowed window. However, furniture is strewn about the building and Scientology paraphernalia is scattered about. North of this was additional staff housing as well as the practice cottage.

But the most beautiful part of Chilocco is the immense lake. A small footbridge with white railings crosses the water. Ducks and geese move through the gentle water. Being that this is the first thing you see after you come up the long drive from the entrance, the stage is set for a beautiful school, set alone on the Oklahoma prairie. Although the campus and school were impressive, lasting and well equipped to continue educating Native American youth well in the future, its decline began.

During the 1960s and 1970s Chilocco was on a track to closure. Enrollment and funds began to dwindle. It was becoming more expensive to house and educate the students than if they were to attend public schools. Chilocco was now no longer serving it’s surrounding areas. In 1972, 158 students were from tribes in Oklahoma, 605 students were from elsewhere, mostly Alaska. Senator Bellman lobbied that the school be closed amid severe budget cuts. In their eyes, the school had served its purpose, it had brought the American Indian into the mainstream of society. And with that there was no longer a need for the institution.

Chilocco also suffered from a series of scandals that plagued the school until it closed. In 1972 Carlton Grass beat a fellow student, Eugene Voight. Grass beat Voight to death in a dormitory. The National Youth Council sent out letters to parents regarding “unreasonable restraints on children, invasion of privacy, inadequate recreational activities, ineffective counseling, illegal detention of juveniles, and lack of parental and tribal control.” They cited the unlawful detention of several girls in the Newkirk jail. Also in 1972, the National Indian Youth Council staged a sit-in in the administration office. They demanded “an examination of all phases of education from curriculum to brutality”. Although, it is important to note, that a Daily Oklahoman article states that the students support the school and that the student council opposed the sit-in and the letter. After this though enrollment dropped rapidly. When Chilocco opened it housed well over 800 to 1,000 students well into the 1950s. Now it barely held 100. Chilocco was dying.

The last class to graduate from Chilocco had only 11 students. It’s dilapidated structures were no longer maintained and the campus was a shell of what it once used to be. At the last commencement ceremony held, Chilocco’s superintendent C.O. Tillman addressed the remaining students “Let’s go out of here smiling and proud if the school is closed. So we can look each other in the eye when we meet again and know we did our best” They were unsure if the school would re-open in the fall. However one attendant at the the event says “the OG&E trucks were there waiting to cut off the electricity, ONG was there to cut off the gas”. It is a very sullen moment to realize that a place that offered many so much hope and determination was no longer a reality. Chilocco closed and the gates were locked.

Chilocco is owned by five tribes: The Kaws, Tonkawas, Pawnees, Poncas, and Otoes. After its closure they sought ways to save the school. They attempted to turn the school into an Indian College but this never came to fruition. They had no other options until NARCANON arrived. NARCANON, which is a Scientology based drug and alcohol rehab center opened around 1990. In much fanfare Kirstie Alley opened the center as Chilocco New Life Center. Alley is a driving force in Narcanon and Scientology They hoped to encompass the entire campus of Chilocco to have the largest NARCANON center in the world.

Based on the teachings of L. Ron Hubbard, NARCANON’s treatments are based on sauna like exposure, where patients sweat the drugs out of their system with heavy doses of vitamins and rigorous exercise. These treatments are not approved in Oklahoma. Thus they never obtained an official license from the Oklahoma Department Health. They only recieved temporary liscenses. NARCANON argued that since they were on tribal lands they were exempt from state law. The surrounding areas also protested the arrival of NARCANON. They leased the land for 25 years but paid nothing to the tribes for the first two. And they also failed to pay the state in back taxes. Narcanon relocated to Lake Eufala in 2001, which is no longer open.

The story of Chilocco is one of bravery, heartache and perseverance. For many it represents the best years of their lives. For others it was their worst. It’s purpose to assimilate is controversial but realize that it was not alone. Many other Indian boarding schools across the country existed for the same purpose. Chilocco at times was hell and at others was heaven. Alumni look back and recall their memories. Their opportunity to better themselves. A school such as Chilocco is a monument to the hardships of the Native American people. Having been forced out of their homes to integrate into an “American” society is a hardship that most often fail to realize. Chilocco is still here though. It is a historic landmark and is apart of not only Native American’s history but ours as well. Chilocco was called “the light on the prairie”, Although its halls are dark and silent, it still shines as a part of every Native American.

“The smoke from the bowl of the peace pipe has died down, yet there is one bright ember still glowing. Keep it alight students of Chilocco”

Gallery Below

| Other Great Resources on the web: | Even More Resources on the web: |

If you wish to support our current and future work, please consider making a donation or purchasing one of our many books. Any and all donations are appreciated.

Donate to our cause Check out our books!

I was among the many who volunteered to attend the first Oklahoma Indian Police Academy in the summer of 1979. Mostly made of men with only three of us ladies. It was taught by some of the most revered law enforcement Oklahoma had to offer from OSBI, FBI and Tulsa officers, even the great Judge Pipestem of the Osage Nation was one of our instructors. It was a grueling six weeks with about half of the men dropping out all of the ladies graduated proudly. Margo Gray also Osage completed a course she required and graduated with us. Many Nations of Oklahoma participated and we even made the Oklahoman in a nice article. I haven’t seen this written about yet, but perhaps I may have overlooked it.

As a child I begged my parents to send me there, but due to what my father endured when he was a young man he refused me.

My great-grandfather attended Chilocco from 1900-1902 aftrr being at Albuquerque Indian Industial School from 1894-1900.

He was on the Chilocco Football Team.

Thank you so much for sharing this pic! My great grandfather is George Baine, bottom right. It’s so awesome to see photos of him!!!

Why people can go see the school?

Thank you for posting this. I know some people loved their experiences at Chilocco but the stories my family who survived their time there are pretty chilling. I say survived because I should have had another Aunt except she died while they were attending the school. She is still buried there on the school grounds. I can’t visit in person, but your photos help me connect the stories I grew up hearing about with a real place.

My maternal aunt went to school there in the years 1964 and 1965. Her memory is vague, however, she remembers a friend that she had and wants to see where she is at today. She remembers her name as “Vida.” If anyone has any information, please let me know. I would like to help my aunt. My aunt is from New Mexico of the Navajo tribe. As a Navajo woman, I too am from NM, went to school in Tahlequah, OK, and now live in Oklahoma. I was provided education and much more and now I am giving back.

My Grandfather helped design and installed the beautiful wood gym floor (back in the 1960’s I think). It is still in great condition today. I went to high school at Newkirk, so I was very lucky to be able to tour Chilocco many times. It literally looks like a town frozen in time. We even took our Senior Class pictures there in 2008. It has disintegrated so much since then. The building that is the background for our photos, has since had its roof cave in, bringing the walls in with it. It is such beautiful architecture, with a bittersweet history. I had hoped the Tribes would have tried to restore or at least preserve some of the buildings, but as of my last visit, that doesn’t seem to be happening.

It was also being considered to be used by the Department of Homeland Security for chemical testing. Thankfully, those plans were pulled when our community and the Tribes voiced our concerns, not only because of the unknown health risks associated with it, but also because of the abuse of sacred land and those who are buried there.

https://www.news9.com/story/36817786/chemicals-to-be-released-near-newkirk

news9.com/story/37062826/american-indian-tribes-opposed-to-chemical-testing-on-chilocco-land

https://www.change.org/p/department-of-homeland-security-stop-chemical-testing-at-chilocco/u/22161738

My aunt Jane Bowman went there.

Wish there was a way to look at names of residents from the 60s.

Beautiful history . I wish they had made it into a historical museum . Great history lesson

What is the meaning of the "Nazi" symbols of the banner above?

Before this symbol was deemed a Nazi symbol it was originally used by native americans, and was later adopted by Nazi's. This symbol is of course called a swastika, which in sanskrit means "well being" and has been used by many indian tribes throughout history. Before the Nazi's began using it this symbol was known to represent order and stability, whereas now this seems to be the lesser known representation as most associate it with a much more horrific representation. If you notice the swastika shown above is facing counter-clockwise while the Nazi's faces clockwise. This symbol was used by Chilocco before the Nazi's adopted it and was deemed too priceless a piece of history to be removed or changed.

My mother attended this school. She was proud of her days there. Even at 86 years old now (2017) she remembers her time with with much love and pride.

My Dad was there and is the same age as your Mom. He was on one of Chilocco's great boxing teams. Grover Murray. He passed away in 1999. I wonder if your Mom remembers him?

My 85 year old mother and her sister also attended Chilocco. They were Beverly and Margaret Wagoshe. They are Osage. My mother loved her days and Chilocco and remembers her days there quite warmly. We attended and Alumnus weekend there in 1968. I was 14 and charmed by the campus but even then it showed signs of dereliction. I new building had been erected that was part dormitory and classrooms. They had a display of yearbooks that I enjoyed looking over. It was in August, windy and quite warm. Great day!

great article this is.

Thanks Yoda

It should have been preserved for tomorrow's Americans to see what was right and wrong with the "assimilation" approach to co-existing with native cultures…

I hope someone can help me. My great-great grandfather attended this school in the late 1800's and early 1900. He was listed on the US Indian Census at the school in 1900. I need help find more information about him. Any suggestions? Thanks!

Look up the DAWES Rolls and see if you find him or another ancestor there.

Although this strict way of life was harsh, many students appreciate how it benefited them later in life. However some do not.

never liked it there,people were mean to me.Glad they closed it.

Hi tom maestas, I attended chilocco 1970 to 1973! I have alot of good memories of going to high school their.

Hello to all Chilocco, Former Students, Former Employees and their families. It is so great to see all the comments posted on this website. And I am so thankful for it. Woolsey(Will) Walking Sky, Class of 1972 was a student at Chilocco for 2 years.(His sister Kay Walking Sky and Corbett Walking Sky attended their also). He was taught by S.L. Morris in Graphic Arts at the Print Shop which was very beneficial to his career. He has talked about the great memories of Chilocco and though it has been years since then, Chilocco was a very important place and time for him. I am Marilyn (Benton) Walking Sky. My parents both worked there also. My father, Mr. Nathan Benton, Jr. was the Vocational Teacher for the Heavy Equipment Class. My Mother, Mrs. Vernis Aline Benton, worked in the kitchen. I know that many of you remember Kitchen Detail, right! Currently my parents are both still living at the age of 84 and Lord willing 85 for this year. Mr. Nathan Benton, Sr.(my grandpa, Willie James, my uncle & Jennie James, my aunt were employees also. This will be the 3rd year that the Chilocco National Alumni Association will have the Chilocco Reunion at Chilocco on campus. It will be on June 5th to 8th, 2014. As you have seen some of the pictures posted on this website, I strongly encourage All of you to come and join us at this time. As Chilocco made history for you, now it needs you to continue the History!.

If you should need more information about the Reunion, please feel free to contact Jim Baker, current President, at jimrbakerb@netscape.net, 405-377-6826 or Emma Jean Falling, Treasurer at 918-266-1626. There are several Chapters in the Chilocco National Alumni Association and I am sure all are willing to help. So to ALL Please Come Join Us from Thursday night Reception (and so many activities in between) to Sunday morning service. If you should know of anyone that might be also interested, pass this on! BELIEVE ME, YOU will have even more great memories to Cherish from this reunion! Sincerely, Marilyn 🙂

Give Mrs. Benton a big hug from Robert Lewis. Class of 70. 4496 Waconda rd. NE. Salem, Oregon 97303

My father (S.L.Morris) taught Graphic Arts at the Print Shop 1961-72.

He was a dedicated teacher who believed in all his students.

Many of my friends parents taught and worked there.

The school was one of my playgrounds. My fondest memory is the Pow Wows on the football field each year. I can smell the "fry bread " now. I see the performances of "Eagle Dance", Hopi , Corn Dance (hearing the shaking noise of the corn). All very magical. The Swans in the lake often entertained me.

I hope one day the facility will be reborn into a new & again important peice of history and encourage the owning tribes to make that happen.

Any of my fathers students that see this, I would love to hear from you any memories.

Sincerely, Rodger Morris

Hello There! This is Marilyn (Benton)Walking Sky! So Glad to see your post. OMG it has been such a long time. I hope that life has been good to you and your family. Just to let you know about Chillocco. If at all possible try to come for the 2014 Chilocco Reunion on June 5 – 8, 2014. We (Me & Will, husband 36 yrs.) will be helping the Chilocco National Alumni Association with the reunion. They have been able to have it on Chilocco campus for the last two years! This June will be the 3rd year there. You may have to reserve rooms in Ponca City, OK or Arkansas City, KS. There is also RV Facilites at the Native Lights Casino.

My husband was a student of your dad in printing. We have often talked about both of you wandering how you might be doing. Both my parents are doing great for 84 years old. With exception of my mom's recent broken ankle but we are getting thru it together here in Texas. There is so much to tell you but I will have to catch you up at a later time. My email is walkingsky@suddenlink.net is you want to reach me. Please see if you can plan to come & you may get to see other employees & Kids! Marilyn 🙂

Hey Rodger it's me again, Marilyn. Still waiting for your email to me. Email address is walkingsky@suddenlink.net. Sure with you could contact me soon. So much to say!!!

Marilyn 🙂

who owns the school now?

I'm looking for Almon Louis Fife. A creek indian, maybe in class of 1936-1939.

Dad,Bert Jacob Wood, attended Chilloco before leaving and joining the army and served in WWII during the whole Battle of the Bulge but I am having trouble finding records of his being there and his history. He was an orphan sent there after some lawyers were able to trick the kids into signing away their home place in Eufaula and I would like to find our if he had a roll number and possibly check that way.

Thank you for any info I can get since he passed in 1999 and mom in 2008 I have very little to go on. He was Sfc. Bert Jacob Wood in the army and was retired and living in Edmond, OK upon his death.

My Mother Delilah M. Old Rock Martin went there from 68 to 70 she graduated in 70, I was wondering if anyone knows how to get a yearbook from that year? u can reach me at j_swifteagle@yahoo.com thank you 🙂

My grandmother Johnnie Ruth Cooper attended this school. if anyone remembers her please contact me. red.dirt.rebel78@gmail.com

Still looking for someone that may have known Edith Etsitty, we did find her picture in the 1953 year book.

Am looking for information on Edith Etsitty , she was in the school in the 50's for sure . Can anyone out there help me ?? we do know Edith, and would like to have moew information on her so that we might get a Birthcertificate for her . does anyone have any ideas how to do that ?

question.. why exactly are there swastikas on certain parts?

What was stolen and labeled as Hitler's symbol of a swastika was original a symbol of many different meanings among American Indians as well as several other cultural groups. http://www.collectorsguide.com/fa/fa086.shtml

Hi again my name is Thomas Blue Back Sr now, I went to Chilocco in 1965 to 1968 it was the best time of my life. I will never forget the time i was there met a lot of friends and i would like to here from you if it's possible. I did see a lot of you all on this net work, one was Elizabeth Chass and other Claudene Boyer. I hope you remembur me, i wish i could go back in time i would stay there forever.:)

Hello….:) to all da Chilocco students, it sure was nice read all of ur comments about Chilocco n yeah it is sad to see how it today.

Hello from the Navajo Nation, Harrison W. Begay is the name..I graduated from Chilocco in 1970, when I turn 18 in June I was drafted into the military (U.S. Army) Vietnam veteran. I still have many memories and good ones while I went to school at Chilocco. Opportunity has not come upon me to revist the school yet but I am hoping some day will come. To all former Chilocco students out there I hope you're all doing fine and safe out there with your families and love ones..May the Great Spirit watch over you and keep you safe.

Hi my name is Thomas Blue Back, I went too Chilocco Indian school in 1966 untel 1967. I had a good time there,if you are a good classmate or friend E-Mail me at thomasblueback@yahoo.com. See you.

:$

Here is a link to a film on YouTube featuring school activities in 1947.

My Grandfather and uncle attended the Chilocco school in the early 1900's. I'm trying to get information on them both. Where and who do I write to, to get the archives. I seem to be down a dead end road. I once had the information and through out the years I seem to have lost it., If someone can help me or send me to someone who can.

Just found my mother (Pauline Stites) in the 1939 year book. She enjoyed her time at Chilocco.

My Grandmother and her sister went to Chilocco. Chilocco's Reunion is going on right now at the campus.

The objective of the school was to integrate and assimilate American Indians into the mainstream of American life. Until the 1930s, the school relied on a highly-structured and strict military regime

i use to fill the vending machines at the school in the 70's and my father-in-law was a teacher there. i went to the golf course many time to play golf watched football games and to the cemetery where half the markers had no names. It 's realy to bad the tribes could not do something to bring it back to life. a lot of carma is still there.

i have been reading about the high suicide and other unhappy problems going on in the south dakota , and group of differant idians . I am looking for to be vouaterring to come and help out as much as i can . i am very invoulved in helping others and i think i have alot of love and experience to share and give. i have been on streets my self and abused and i think my stories and helping out with them would do wonders. i have alot of love to give. could you tell me if there is eny camps ,youth or adut places i could help at in ok thank you and God B;less My email is i4dirtpooroke26@yahoo.com and cell nub is 9187123553

JUCO Student 1963-65 was a very good time at Chilocco IS, many good memories meeting Indins from all over the USA.

Your parents were the best ever, and I do mean that from the botton of my heart. My brothers attended Chilocco before me and they always talked about Mr. & Mrs. Bushyhead. When I went, they were the best that you wanted people to meet in the whole wide world. My Mother and my older sister also attended Chiloccco and their stories made me want to go there. The campus was beautiful and it was a city within itself. Everything and everyone were right there. Our campus was the absolute best, prettiest, cleanist, and we all loved it; everywhere you looked, it was Native American.. AIM was there in our lifetime and we saw it all. Wow, it still amazes me that we experienced it all first and foremost; the Fish Pond, the Waternellon feeds, Playday, Sadie Hawkins, Student Union Dances. etc. etc. etc I met and know the best people in the whole wide world; and no, it wasn't a school for orphans. Our memories and our hearts and soul are and will always be Chilocco Indian School. Always and forever! GO CHILOCOCCO! Those in charge, please do not let it deteriorate any further. Too much history is right there………

Hi my name is thomas maestas and I attended in 1970 to 1973! Hello to all you former students!

i am trying to locate the old records my father went to school here in mid to late 30s.Can anyone tell me where to start to find his old school records. Thank you

WOW!!!! this is all so amazing ! just thought 'id typ in Chilocco again an see what i could find, an i get to read some intresting stories bout Chilocco, where can i find some updated photo's of the school? it has been ages since i was there, but Chilocco will for ever be in my Heart, i had good times there. students were all like one big family an we were civil to each other an treated one another with Respect. i wish to find some old school mates here myself. Lona Frank, Mary Teneiro seelkoke, archie seelkoke,Karolyn Takes The Horse, Karen Takes The Horse, chenda Yepa Largo, to name a few 🙂

Paraguay vs Greece live stream soccer where?. . Paraguay vs Greece live where?. . Paraguay vs Greece where?. . Paraguay vs Greece live streaming where?. . Paraguay vs Greece live stream tv link where?. . Paraguay vs Greece live stream free video broadcast where?. . Paraguay vs Greece live online where?. . Paraguay vs Greece live on PC where?. . Paraguay vs Greece live free video telecast where?. . watch Paraguay vs Greece live stream tv channel where?.

Who cares?

My Father taught at Chilocco starting in 1957, for 20 years. He retired as the Vocational Department Head. As a youth, growing up on campus was an experience rivaled by none other. Its' current condition is abhorrant but my memories remain fresh and pristine.

I believe my father worked with yours… Berklie Perico. What memories

The Chilocco Football and Wrestling teams played against the Douglass High School (Douglass, Kansas) teams over the approximate years of 1955-1962. My father, "Pete" Schreiner was the Superintendent of Douglass High School (starting in 1952-66). I recall as a very young girl riding in the car to Chilocco to watch football or wrestling matches at the Chilocco campus. Plus Chilocco also coming to Douglass, Kansas a couple of times to play us on home turf or wrestling matches or tournaments. The Chilocco boys were very strong, quite intimidating, and tough competition for all.

ne of ther football and wrestling coach was Louis Valdez (59-62). I recall Chilocco won most (if not all) football games against us but the wrestling matches were different and quite the event!.

The wrestling matches were quite intense with much eye contact and intimidation in body language by the wrestlers and of course, great pride acknowledged to each individual winner of the weight class as this was really an individual win plus a team win. We would win some and loose some but the matches were always wrestled well with excellent sportsmanship displayed by both sides.

At one meet, we drove to a wrestling match in very cold weather riding in a purple painted station wagon (about 1958-60) with a school's bulldog mascot painted on the sides. It was the first time I had actually seen a mowhawk haircut or a "real" American Indian as a very young girl. The boys wore black, white, and red letter jackets and were very muscular and serious looking. I was very impressed and it was an exciting wrestling match to watch because my brother was a wrestler. I do not recall how he did but there were several Chilocco boys within the years Douglass wrestled against Chilocco in the 128 132, 145,154 weight classes that the Chilocco wrestlers were hands down the best in the Midwest (not just the state). Of course, this was before the schools were unified and broke down into classifications so if you won state or regionals, you indeed were the best in the state.

I do not know if any of the readers were wrestlers then but it was always a great pleasure to be able to go to Chilocco and have them come to Douglass to compete against us! Not until I have read this history did I realize what was happening to the American Indians and these students. I am quite sad…and embarrassed.

I am also sad to learn that the school was closed down as it was only my thoughts of those early days tonight that I looked on line to see what has happened to the school. Those boys were tough!

As a sidebar, I do not recall seeing other girls or children at the wrestling matches. From what I recall, the matches took place in a very small, very warm gym as it was quite cold outside; the football game weather was cold, but well attended by locals. I would like to go back to see the school but I understand that is not possible. This is at least a fun and very respsectful memory for others to share that many still recall the pride of the football and wrestling teams of Chilocco vs Douglass High.

I have been too visit Chilocco, my auntie and other family went there and graduated from there, I had a lot of questions about the spirits in that school, I could feel them as soon as I entered the gate of the school, my grandmother has told me stories of hearing their names called and yet when they turn around no one is there.

Hi Michael, i went to Chilocco in 72, i never had any thing bother me, but i made a visit back in 96, a promise i made to myself when i left. i had a feelin there were Spirits watching over us , let us go have fun on sat no security, sun we got stopped by security.. after all was done the day b 4 , we were just goin take a few more rolls of film up lol.. but yup! the Spirts there r good, least they were to me lettting me be invisible that sat. ask my fren she will tell ya 🙂

Hello everyone, I attended Chilocco from January 1968 until January 1971, that was the grandest time of my life, I made many good and lasting friends there and learned all I need to know about life and how to buff floors with an electric buffer! I worked many hours in the chow hall and I was a cheerleader for three years, I think we only won a handful of games that I jumped around too. I didn’t know a thing about the game of football or basketball or anything ‘sporty’ I eventually learned though. I would like to see some of the 1970-1971 alumini at the reunion coming up. God bless you all!

Darlene,I don't know if you will remember me, I was at chilocco only 2 years as a freshman and sophamoremy name is Greg Savage from Alaska. Pardon my typing i'm just learning this computer stuff. i would like to here from you if you are the person that i knew

Good evening all you Chiloccoans. I graduated from Chilocco January 1967. I'm enrolled Yakama from Toppenish, WA. During my 3 years at Chilocco was the best years of my life. I went back twice since then and the last time was in 2004. It was so sad how the place was run down with weeds all over and the Oval was cracking. But Home 5 and the Student Union was still in good shape. i haven't been back since as I would rather keep in mind the good times and the great friends I had while I was there. I learned so many valuable lessons that I keep in mind and pass on. If there was a job opening there, I would go back in an instant.

Good luck to all & write to me sometime……..Georgett Long-Abrahamson …lenabe1@yahoo.com

my father Clyde Wilson also is an alum of Chilocco but the only i know is that he was a freshman in 1964. He said he graduated from that school also. I am hoping to learn more about Chilocco school because it seems to hav such a rich history

Like a lot of other kids; Chilocco was my salvation. I have always regarded my high school years as the best years of my life. I would not trade those years and friendships for anything. It broke my heart to see how things had changed there after only 5 years and I don't think I could handle seeing what it looks like now. I love the memories I have held in my heart and soul. I lived there for 4 wonderful years with the classes through 1964-1967. Mrs. Means and Mrs. McGilbra raised me and I love them for it. Chilocco- 4 ever in my heart.

You must be talking about my Aunt Grace McGilbra, she was a sweetheart. My father Jerry McGilbra along

wife his brother Carriasco and my Aunt Shirly attended Chilocco.

Hi Libby, this is Loretta from Fort Hall. Haven't been in touch with you for a few years and hope things are going well with your family. I also have the fondest memories of Chilocco(graduate of 1967) and am always telling my grandchildren about "my" school. In fact, my oldest granddaughter graduated from Riverside Indian School last Friday, 5/18/12(same day of our graduation 5/18/67)! We drove thru there and was disappointed that it was closed and locked up. I so wanted to show off my school but maybe it was for the best with all the neglect that has happened to the grounds and biuldings. Have been thinking about going to the the reunion but I would like to see one closer west since there were alot of kids that attended Chilocco who are from the western states. My email if anyone would like to contact me is lpedmo@sbtribes.com.

Hi Elizabeth Chase from Thomas Blue Back Sr, I was looking at my computer when i noticed your comments,i'ts been a long time since i heard from anyone from Chilocco, it seem's like i was the only one around here. It would be nice to hear from you, if you remember me. Thomasblueback@yahoo.com.

Karen Haymond, Class of 1967… Attended 1966 & 1967. Chilocco is the most wonderful time in my life. I always tell stories of Chilocco – Home 5 and how much fun I had, when I was at chilocco. Lots of my classmates are still my friends and we keep intouch with eachother. Living in Pawnee, OK and attend the Chilocco Reunions. I had a twin sister, sharon who went to Chilocco in 1966 and I return by myself on 1967.

I just wanted to express some of my thoughts and feelings. I work for the Pawnee Nation, Enrollment Department, Pawnee, OK and I miss all my classmates and sometimes I run into someone from chilocco and we all have some good stories to tell eachother. Chilocco Indians…. Forever !! krhaymond@hotmail.com

I peridocially visit the campus to help clean the cemetery. This was home and brings tears with each visit as I met my wife here, who is now gone after 49 years of marriage. Just a few years ago the buildings were still intact. Not so today. But memories will be cherished forever. Will it be restored 10 years from now, or will it still be just talk?

Two grandpas and one grandma went here. One grandpa spent more time on the run in the 1890's than in "class".

I had a Grandfather who taught Agriculture in 1930 or sooner. Is there any way I can find the names of any faculty that far back?.

My daughter and I drive by the sign for Chilocco Indian School every time we go to Native Lights Casino. We have always wondered what the school looks like. It's so sad seeing the pictures. If I were physically able, I would volunteer for free to help clean up the place. I have always been fascinated with the Native American culture.

People should Read on the History of this Tragic Place.

After the closing of Chilocco in 1980, I didnt return until 1989 with my then wife who worked for Narcanon it was a very sad experience to see the grounds so empty of life. I saw the empty run down buildings and could remember when the students and faculty housed them with such pride and honor, along with the music. It sadened my heart to see it in that shape, but i will always have such great memories.

Both of my parents worked at Chilocco from 1958 to the closing in 1980. I was born in El Reno but was raised at Chilocco as were my other siblings. My dad, Victor Bushyhead worked in Agriculture and my mom, Clara Bushyhead worked in the girls dormitories. If you went to Chilocco in that time frame YOU KNEW MY PARENTS. I grew up with Chilocco being my playground and with that made many lifetime friends that I still hold dear today. I know they miss Chilocco just as much as I do, and I am sure as anyone who had ever lived there does. Some of my childhood memories are of the watermellon feeds, harvest time, playdays on the playground, the enrollment of the new students, the non-stop greyhound buses being bumper to bumper, the pow wows and the football games.

Hey Darwin, hows ur Mother? she was my Matron in 72 , OMG this is so Amazing !!! i finally found some one i know LOL.

Are you related to the Bushyheads in Arkansas City? I grew up with and spent a lot of time with Gary. I left in 1975 and go back periodically.

Is there anyone we can talk to, to let us visit?

Is your sister Shanista? My grand parents lived there for 35 years…the Gregorys. I loved Chilocco

I can't believe I've made it to 74 years of age, it's getting dark ha, ha

How many of us are left outside of history alone? I'm still kicking call me Dennis James at 19184575516 if you are still out there and remember days past. It seems we are going extinct , Bill my brother, Doris my sister, Margie oldest sister, have all past all. Does anyone remember how beautiful Betty Buffalo Head was back in the early fifties? I wonder how many of our bunch are still around, it is sad that our breed is so few now.

Dennis,

How wonderful to know you are still with us. I've never lost my memories of you. What a wonderful

part of my life was Chilocco. Nothing has ever come close to those times as far as pleasant living.

No worries, it was great.

Here is my web page: http://stonescry.tripod.com/ Go to Electric Scotland from there to see what I'm

doing, in my old age. <grin> I write daily or so, more or less at the forum with Electric Scotland, so

you can see what's going on with me today: http://www.electricscotland.org/forumdisplay.php/…

Donna Jones Flood, class of '55

hello Dennis I will call you. what do you want me to call you?

Did you ever know Edith Etsitty (Edie)

Dennis do you remember the following people? Beverly Powless OnondagaNation, Elizabeth Powless Onondaga Nation, Martian Powless Onondaga Nation, and Billy Harrison Navajo Nation?

I beloved up to you will obtain performed proper here. The sketch is tasteful, your authored subject matter stylish. nonetheless, you command get got an impatience over that you want be handing over the following. ill without a doubt come more beforehand again since precisely the same just about a lot often inside of case you shield this hike. – Elegant London Escorts, 65-67 Brewer Street, Floor: 2, London W1F 9UP. Phone: 020 3011 2941

Many thanks for your info about Music Instrument

Does anyone know what year Lousie Fixin Cameron graduated from Chilocco Indian School?

1950 – I have the yearbook with her picture in it.

Some of my most memorable moments in life were @ Chilocco. My grandfather, Dee Gregory worked @ Chilocco for 30 years. My mother and her sisters grew up there. It was a sad day when they had to move off the grounds. Every chance I get I return to look at whats left and talk to my kids about what a wonderful time I had visiting my grandparents and aunt every holiday and summer. I will never forget the good ole days @ Chilocco.

Jan:

I remember taking Janice Dee, Greg, Jill and Todd there. We stayed at your Grandparents and had Thanksgiving. I believe that the year was 1979 or 1980. I think that you had left home by then and that was the reason you weren't there. I look at the photo's often.

I learned alot from Mr Gregory

My grandfather was a wonderful man. I remember his laugh most of all and his gentleness and he was a great listener as well. You were so fortunate to have learned from him as well. Thank you for the compliment.

I bet your Moma was Janice or her little sister. I graduated with Janice, she was a dear friend, and a beautiful and gracious young lady. I still miss the fun times we had in high school, and getting to visit with her at our class reunions. She left way to early, guess God needed a beautiful angel to play the flute in his band.

Fanchone Myers

yes my mother is Janice Dee. I miss her so and have heard so many good things about her. I loved chilocco as well.

Hi My Name is Carol Afraid Of Hawk. I attended Chilocco in 78,79, It was the best years i ever attended at school If any body that was there at that time maybe you remember me they used to call me Munchkin. My adress is box 282 Fort Yates N.D.

I remember you. I am Joanne Twoteeth from Helena, Montana.

Hello,

Munchkin I remember you, Cheryl Warrior.

I attended Northern Oklahoma College in Tonkawa and some locals took me and a few friends out there one night. Hands down the scariest and most interesting places I've ever been. Just looking at the picture and reading the article gives me chills all over again. Anyone I've talked to that has been there has a story about paranormal activity and just as we crossed back over the bridge to leave in my friends 2007 truck (brand new at the time) it died and would not start. We sat there for almost an hour before it started up again! Scaryyyyy stuff!

My great-aunt Epsie Louise Ladner was a Chilocco graduate of 1932, I believe. Would you have any information on her. She was president of her Baptist Youth Club there. I have pictures that were passed on to her sister, Ruby Ladner, after she passed away. I also have pictures of students that I believe graduated with her. Some pictures are taken of her and her sister on the campus. I also have a postcard of the football boys of 1932. If you have any information of her or Ruby, my grandmother, please contact me! (580 276 4226) or text or call my cell phone (580 812 1920) thank you!

Chilocco holds a special place in my memory as I was a freshman there in 1979-80. The last year it was open and operated by the BIA. My dad graduated from Chilocco in '57

So yes I have an established Chilocco blood line…….

call me anyone if you remember chilocco from 1965-69

(907)230-5628

Pius Savage

Sorry for a late reply. I am not that technically challenged. I replied to your e-mail at my address. Sorry for the discrepancy. Glenice (Evening) Teton remembers you. We work here at the attorneys office in Fort Hall, Idaho. I remember you. Hope all is well with you. The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes are having their festival starting today through Sunday. Plenty busy here. Catch you later. Claudene

Hello Pius good to see your still with us.. Frank BC

i have memorys of you guys sitting around the dorm room playing cards.how has the world been treating you oh pius savage?

🙂

I have this CD. Great choice for your slideshow.

Very interesting. I have had the opportunity to be on most of the 5000 acres that make up "Chilocco" in working with the various tribes. I was never on the main campus though. I was amazed at many of the agricultural buildings/barns that were build off the main campus and are hidden in the trees. I would have loved to have been able to photograph those buildings. Also it is worth mentioning that there were many small erosion structures all over the country around the area that many older farmers say are remenants of Chilocco students learning stone work by building those erosion structures.

I am fascinated by this place. I spent all morning researching this place, and it seems that since it closed its doors in 1980, it has served some interesting purposes. Apparently Chilocco operated as a Narconon rehabilitation/detoxification center for a while I believe in the 90s, which was run by the scientologists. Then up until recently it was used as a military training facility. Such a large and interesting campus, I would love to go see it and take pictures. I tried to find anyone affiliated to get in contact with to get permission or see about a guided tour and the closest I came to contact info was some phone numbers for the various alumni members. Even the reunions aren't held there, so I am beginning to think this place is pretty much restricted.

I used to live close to this school but never took much interest in it. Thanks for the info, quite enlighting

My father taught math their in 1968 and he always spoke of how he love the students he had. It's a shame that it's gone. Bill

Hi. My father (lincoln morrris) taught printing 1961-72. He too lived & was very dedicated to his students

Rodger Morris

i hope that place goes back to the earth from which it came or made into a memorial like a holocost museum

I have never been to the school and never seen pictures of it before. I live close to it and never even knew it was closed but always wondered what it looked like inside. Thanks for sharing this with those who would have never seen it at all.

I attended Chilocco from Sept. 64 to May 68. I met alot of people and treasure each one that are still alive today. Our school might be in ruin but our memories can never be taken. I can honestly say I truly loved being there with all my Chilocco family. I miss those that are gone but loved all.

Yes, very interesting place. At the time I was there, I was entranced with the natural world surrounding the school. Very different from my home lands in Idaho. Inside, I made friends. But my dreams are still of the trees–which had very interesting objects growing from them, the insects and the sky-the weather was fierce at times but also fun. I didn't learn much there from a western educational perspective.

Wow brings back old memories of my two years at Chilocco. Really sad to see the abandoned buildings………thanks for sharing

Wow, sure brings back memories of my two years at Chilocco. Very sad to see the abandoned buildings. Drove through there in 1997………..Thanks for sharing the video

Some of my happiest memories were of Chilocco,teachers, friends made & bonds kept. It was a chapter in my life I will never forget as it made me a stronger person. I will forever endear those moments and memories to my heart. I thank all of those that had a hand in making those memories. We are still a family, no matter where we are or how far apart. We still have that bond. I Love Chilocco Indians!!!

Chilocco is a place where I return to in my dreams. I attended Chilocco four years, 1964 to 1968. It was a beautiful school. There were so many tribes there. It was a learning experience I'll never forget. I missed being at home but the friendship and warmth from the students held to me like a blanket. Chilocco became my home away from home.

I learned how to type in my sophomore year. I could have excelled in the sciences, or the math classes, but I was distracted just by watching the seasons in which we lived. The staff and teachers were good people. On occasion I did "hours" at the dorm. Fun stuff.

HI;

DO YOU REMEMBER ME pIUS SAVAGE.IF YOU DO SEND ME BACK MAIL.

PIUS SAVAGE

Yes. I remember two brothers (?). Thanks for the e-mail. Claudene

Glenice (Evening) Teton remembers your name and your brother. We work together in the Tribal Attorneys Office at Fort Hall, Idaho. I remembered seeing you and your brother but had not met you in person. Glenice's brother, Sonny Evening, was acquainted with you. He is now deceased. Thank you, again.

Claudene,

Very interesting indeed to see your posting. I don't know if you remember me as a friend when we were at Chilocco. Since Chilocco, I served in the army in the Vietnam War, went back to school (University) for seveal years and received my Ph.D. Now, I am Associate Research Professor at UNM, Albuquerque and Adjunct Professor in the Dept of Physics and Astronomy, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff. I assume you are in Idaho and fully grown. I would like to hear from you via email should you receive this message.

I remember you, (Dr.) David Begay (Sr.). Thanks for the post. My e-address is claudene_boyer@yahoo.com. I'm not a degreed individual as you have become. I'm proud of you. I'm glad you had the incentive to become an intellectual. B) I'm infamous and loving it.

I don’t know if you remember me (Janet Bitah/Etcitty). I was reading thru these comments from different students, and it’s so nice to hear from them. It’s true some night you would dream like you’re back at Chilocco. I always treasure some of my friends still. Anywho, glad to hear from you. I was there from 63 to 68, and made lots of friends. Miss you all and Chilocco.

I attended Chilocco Sept. 1964 and graduated January 1967. At that time, there were 100's of students and most of them were arriving from Alaska. My most precious fond memories were of my high school years spent there and the many friends I made. I talk about it yet to my grandchildren.

Your right Phil, we were at one time a huge family!

Hi Georgette. My father (Lincoln Morris) taught at the Print Shop during your attendance.

His students produced all publications & the Annual Yearbooks.

He loved & was very dedicated to his students as where many teachers.

I'm glad you too have fond memories.

R Morris

I attended Chilocco Sept. 1964 to May, 1968.

The place was in it's full glory days than.

I've met and made so many friends from

different parts of the U.S. and Alaska. I

still have these friendships to this day.

It's like I became a member of one huge

family. For this, I'll always rmember and

love my days at Chlocco.

My father had attended this school his name is Marcus Arthur

My Dad and his siblings, along with their Mom and Dad spent many growing-up years at Chilocco where my Grandfather taught. I have found many pictures of the grounds and buildings. Very interesting; only wish I had asked more questions and knew more of the answers.

almost brought a tear. Chilocco stands as a testament to the 20 Century Oklahoma Indian. My mother graduated i the early 50's, my uncle was a coach, and many other family also attended. I will share this and hope to one day purchase the DVD with all the photos and yearbooks. AHO!

yup i went looked at the photo's of the School what a crying SHAME that is to just let it go, an a historic Place at that? SHAME SHAME SHAME !!! wish i'd hit the almighty lottery, i'd get it back to where it should been all along in Good condition an students still went to school there 🙂 Chilocco will 4 ever be deeply in my heart

Hey Kelly, I say ditto.Was very blessed to attend this years reuion on campus .Looking forward to next yrs.We need to organize a pow-wow maybe fall 2013.Lets revive Chilocco.Go Indians.Kimberly Saul

Wow. I'm impressed. You guys put a lot of work into make this absolutely amazing! Thanks for sharing this place on your site 😀

http://chilocco.yuku.com/forums/66/t/Public-Forum…

These tribes have let this place go for 30 years. Plus let drugheads in to tear it up.

Now they are begging for help to fix what they have let go of.

After 30 years under these tribes control it looks like this.

What will it look like in another 30 years.

A $100 water leak when it started has now turned into a $300,000 repair.

If you’re not going to donate then don’t say shit. I don’t think they just let drumheads in to do what they wanted. You sound like ridiculous!

Awesome article, the History of this place is amazing, it would be a wonderful story if former residents could be located and their stories published.

Keep up the Great Work and God Bless!!!!

sincere thanks to all who contributed to this posting; it’s stunning

Thank you Tsianina! It was a pleasure to read your book as well! It was fascinating and full of such great stories and information.

I remember tha scandals that happened at Chilocco. A relative of mine went there in the 1970's. Although it was never reported aparantly a student hung himself in the gym. I hope his would is at rest.

I live near Arkansas City and pass this place alot. I had always seen the outside of it growing up. Very cool, I didn't imagine it like that. Though it had a very seedy reputation among the kids in AK city.

I wonder what it would be like to actually go to an Indian school as a student. I know that several across the country are still open. I would imagine that it isn't as strict, but definately not easy. Any comments?

hello I have been to a Boarding School at Flandreau, SD. It wasn't too bad they weren't as strict like back in the old missionary days. I enjoyed it got ayway from home met new people from around Indian Country. Only thing was that you have discpline urself to do homework but, I managed to get my done.

in 1980 new laws and regulations were put in place. it carried alarge impact on all state and gov “schools”. they did’t close because the kids were mainstreamed! the cost was greater then the need. these places were just mini-prisions. I was a kid at one of the fine oklahoma “school’s” for children. it wasn’t all that fine after all….

That’s strange. I was THERE in 1996 as a “student” at Narconon. As far as I know, It’s still Narconon Arrowhead.

Narcanon is no longer at the location. It is patrolled 24/7 by private security with the Council of Confederated Chilocco Tribes.

Did you "sweat it out" LOL Not to be rude but did it work? What was Chilocco like then? Did you use all the buildings like the cafeteria and the auditorium building? Very cool!

ya..i was there in 96 and 98 and sweated it out….it was nuts…but man, it was a cool place…creepy…but cool

We visited last January and the place was overgrown and in comlete dispair. I’ve done a lot of research and learned that the state of Oklahoma is (or was at one point recently) considering renovating the place and re-opening it as another school/college/historic site. There are also yearly alumni reunions in the summer months and a group of volunteers that tends to the cemetery. Fiend, if you visited in August it was probably an alum group prepping for the reunion.

I have many more pics, but am unsure where to contribute them. The forum?

Yeah, make a post in the forum. I definately want to see more pics.

This location is full of history, you did a great job putting all this together.

Is there someone I would need to contact to beable to go inside the buildings? If so please contact me at ppighosts4@yahoo.com

Thanks so much.

Liz

In the related article I wonder if the Inidan children were really “clamoring” to get in.

actually the children had no choice so as for 'clamoring' i dont think so.

Great photos with fitting music. Good job!

Hell of a post guys. Hell of a post. Amazing job.

Thank you for publising this. There are existing efforts underway to preserve this important campus, and they need help. We have developed emergency stabilzation plans for Haworth Hall. The funding required to prevent the collapse of this structure is $300,000.00. If you would like to be a part of preservation efforts, please contact me for additional information. I can be reached at (405) 360-5818.

I am so proud of this project & happy to be apart of it! Congratulations to all the rest involved, We Did it! I am ecstsatic that we could document this fading piece of Oklahoma history.

It's a story that has to be told, one that most Oklahoman's have never heard. And not only is it Oklahoma History, it is a part of our National History. It is an amazing place with an equally amazing story. Enjoy!

"FADING piece of Oklahoma history"

is correct!!! http://chilocco.yuku.com/forums/66/t/Public-Forum…

I enjoyed the video very much, i just wished that it could have been a then and now showing. It was scary at times while watching the video and remembering the day back in 1979-1980. Brings back some good memories. Again thank you. Member of the Caddo/Seminole Tribes.